Dan Cook, Sunday Tribune, 8 September 1991

LIFE regularly presents one with surreal experiences – chance encounters that flip the switch on one’s grasp of reality.

Described as ‘as beautiful as the encounter of an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissecting table’, surrealism was the art movement (between the two world wars) which was almost emasculated by Salvador Dali’s tawdry posturings. He consciously created the vulgar image of surreal ‘weirdness’, unfortunately associated with disturbed minds.

The spirit of surrealism is, however, a particularly noisy poltergeist that will not, like a genie, allow itself to be safely bottled within conventional thinking. The enduring popularity of works such as Don Quixote, Alice in Wonderland, and, recently, Twin Peaks can be as ascribed to the recognition of the authenticity of the bizarre atmosphere they create – part wakefulness, part hallucination. These ‘alternative’ realities are common experiences, deeply rooted in the collective unconscious.

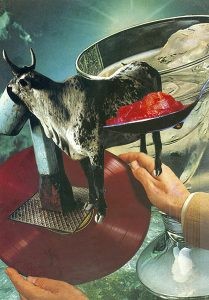

‘Chance Encounters’ is an exhibition (presently on show at the NSA) of laser prints by Fran Saunders. These prints are derived from collages of dismembered magazine photographs, seamlessly reconstituted into surreal images of dislocation. The effect of the laser printing (a new method of coloured photostating) on Saunders’s work is to integrate the separate parts of each collage, thereby enhancing its ‘reality’.

One feels perfectly safe in confronting the small works – as Alice did, following the rabbit down a hole. The brightly coloured prints, and mass-produced plastic frames, are seemingly cheerful and contemporary. But viewer, beware ! These are all part of complex intellectual concepts that seduce the viewer into dropping his defences. Each work is booby-trapped with myriads of landmines – set to undermine, in teeter-toy subversions, any careless footholds in reality.

The viewer’s defensive pretensions are the very hook that renders him vulnerable to Saunders’s probing images. Glib assumptions made – when first seeing the work – mockingly explode on second, or third, viewing. The mockery is, however, self-inflicted, since the artist is curiously absent from these intensely personal works. One senses that the images were made to satisfy some inner compulsion, but that Saunders is too discreet to impose her preoccupations on her audience. She functions as facilitator; images seem to have welled up, rather than having been thought out.

Saunders’s taste is impeccable – she faultlessly gauges the emotional pitch of each work. Nevertheless, she courts disaster as she sails disconcertingly close to the winds of kitsch that blow through the collages. That is, of course, another ‘hook’, ‘game’, call it what you will. One picks one’s way through that particular mind field / minefield, only to find that this preoccupation with taste has blinded one to other landmines.

The gallery is appropriately situated in a shopping centre – as I left, I met a woman carrying an empty birdcage containing a large bunch of keys. Chance encounters like this prove that the poltergeist is alive and well, and living in a reality disconcertingly close to yours.